- Home

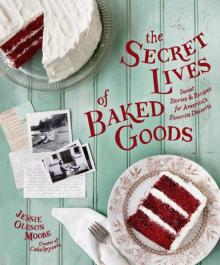

- Jessie Oleson Moore

The Secret Lives of Baked Goods Page 4

The Secret Lives of Baked Goods Read online

Page 4

HOW DID DOUGHNUTS GET THEIR HOLES?

THERE ARE MANY TALES that attempt to explain how doughnuts got their holes—one even suggests that it was the result of a Native American hunter’s errant arrow, which missed its mark but speared an unlucky pilgrim’s morning snack. But most tales point back to a man named Hanson Gregory.

One variation goes that, as a boy, he’d been watching his mother frying doughnuts and had noticed that the centers always remained partially uncooked and doughy. “Mother,” he said, “leave a hole in the center.” Laughingly, she obliged him—and never went back to the old way.

Here’s another unlikely but delightful variation: Gregory enjoyed munching on a doughnut while steering his boat; one night, facing rough seas but not wanting to discard his treat, he speared it onto the spoke of his wheel, so that he’d be able to come back to it after he no longer needed both hands to steer. Another tale goes that Gregory purposely poked a hole in the doughnut to lighten it up “because he had already lost six men overboard due to the heaviness of the doughnuts.”

Of course, the lore surrounding Hanson Gregory gets even more street cred based on the fact that he has a historical plaque dedicated to his invention. It’s true. In Rockport, Maine, you can find a marker inscribed with the following: “In commemoration. This is the birthplace of Captain Hanson Gregory, who first invented the hole in the doughnut in 1847. Erected by his friends, Nov. 2, 1947.”

Of course, it always makes me smile to hear the explanation that “the hole is so the calories can fall out.” Hey, whatever it takes to help you enjoy your snack …

THIS FESTIVE CAKE—BAKED UPSIDE-DOWN and turned before serving to reveal a circle of pineapple rings studded with maraschino cherries—is a clear example of 1950s Hawaiian kitsch, invoking idyllic fantasies of luau parties and tiki cocktails. Only one problem: The cake wasn’t invented in Hawaii—it was invented in—wait for it—Virginia.

Putting the fruit on the bottom ensured a moist, caramelly finish; overturning the pan and letting the topping seep deliciously into the cake ensured that not a morsel would be wasted.

Now, this is not to say that the State for Lovers invented the idea of turning a cake on its head. Upside-down baked goods preceded the famous pineapple version by many years—the art of inverting cakes to reveal toppings is a practice that dates back as far as the Middle Ages. By the 1800s in the United States, they were commonly known as skillet cakes, referring to the pan in which they were commonly baked. This method was born of necessity, in a time when ovens were not reliable for baking cakes. Putting the fruit on the bottom ensured a moist, caramelly finish; overturning the pan and letting the topping seep deliciously into the cake ensured that not a morsel would be wasted. All manner of fruits were used in these skillet cakes: pears, peaches, cherries, and famously, in the form of Tarte Tatin, apples.

There were still a few things that had to happen before upside-down desserts would become a symbol of the Donna Reed homemaker lifestyle. First, in 1901, Jim Dole established the Hawaiian Pineapple Company (now Dole Food Company, Inc.) and began marketing canned pineapple. In 1925, the company sponsored a contest calling for pineapple recipes of all kinds. They pulled out all the stops and assembled an all-star cast of judges for the event, including staffers at the Fannie Farmer Boston Cooking School, as well as from Good Housekeeping and McCall’s magazines. The prize? The recipes would be published in a cookbook titled Hawaiian Pineapple as 100 Good Cooks Serve It, with a $50 cash prize for each of the winners.

Here’s where something amazing happened. Of the 60,000-plus submissions, a whopping 2,500 were for some variation on the pineapple upside-down cake. A few too many to call coincidence, it’s clear that the concept had already been making the rounds in home kitchens. But the Dole contest gave the concept and recipe widespread visibility. The best recipe, the judges concluded, was the one submitted by one Mrs. Robert Davis of Norfolk, Virginia.

Following the contest, the recipe appeared in lots of magazine ads, and pineapple upside-down cake became a popular hostess dessert. But in the 1950s and ’60s, there was a huge surge of popularity for the dessert. Why? Likely the timing: With Hawaii’s statehood made official, there was sudden interest in all things Hawaiian, either real or imagined (including exaggerated tiki motifs!). And what more delicious way to celebrate the birth of a new state than with something sweet?

Pineapple Upside-Down Cake

EXTREMELY EASY TO PREPARE, this cake is fun to make in a clear Pyrex dish, because after baking, when you flip it over, you can witness the toppings dripping like sugary stalagmites onto the cake below. Though not necessary, it’s very fun to serve the cake alongside beverages sporting mini umbrellas.

Makes one 9-inch square cake (9 servings)

FOR THE TOPPING:

⅓ cup (5 tablespoons) butter

⅔ cup packed light brown sugar

9 slices pineapple rings in juice (from one 20-ounce can), drained

9 maraschino cherries, stems removed

FOR THE CAKE:

1½ cups all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

½ teaspoon salt

½ cup (1 stick) butter

½ cup granulated sugar

½ cup packed light brown sugar

2 large eggs

¾ cup whole or 2% milk

1. Heat the oven to 350 degrees F. To make the topping, place the butter in a 9-inch square baking pan, and set it in the oven until melted (it’s fine to do this while the oven preheats; the butter will melt quickly). Remove the pan and gently shift it so that the butter covers the entire bottom of the pan. Sprinkle the brown sugar evenly over the melted butter. Arrange the pineapple slices over the brown sugar; you should be able to comfortably fit 3 rows of 3 pineapple rings in the pan. Place a cherry in the center of each pineapple slice.

2. To make the cake, in a medium bowl, sift together the flour, baking powder, and salt. Set aside.

3. In the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, cream the butter and sugars on medium speed until fluffy, 3 to 5 minutes. Add the eggs, mixing until incorporated. Add the flour mixture alternately with the milk, in 2 to 3 additions, pausing to scrape down the sides of the bowl with a rubber spatula after each addition. Beat on low speed until fully incorporated. Pour the batter into the pan, taking care not to dislodge the pineapple or cherries.

4. Bake for 45 to 50 minutes, or until a toothpick inserted into the center of the cake comes out mostly clean. Immediately place a heatproof serving plate upside down over the pan; in one swift, sure motion, flip the plate and pan over, so that the cake is now on the serving plate. Leave the pan in place for several minutes so that the brown sugar mixture can drip over the cake. After it seems as if there is no more dripping to be done, lift off the pan. Serve while still warm. Store the cake loosely covered at room temperature for up to 2 days.

OF ALL THE CAKES IN THE BAKERY CASE, red velvet is the flashiest: a vibrantly brazen red cake topped with a striking coat of contrasting fluffy white frosting, and a name that sounds like it could belong to an exotic dancer. In spite of its eye-catching appearance, though, the flavor is surprisingly delicate: the cake has a light cocoa and buttermilk flavor—not as assertive as many chocolate cakes, but more distinctive than a vanilla cake. It gets most of its zing from the cream cheese frosting, which is its most popular topping. It’s one of those cakes that some people love and some people loathe, but everybody notices.

The cake’s color is a mixture of science and a sprinkling of man-made magic.

To the uninitiated, or to those who have only had an inferior version, the cake is not merely a red-tinted vanilla cake—or at least, it shouldn’t be. The cake’s color is a mixture of science and a sprinkling of man-made magic. A reddish hue does occur naturally, based on the chemical reaction between the alkaline ingredients (baking soda, baking powder) and the acidic ones (cocoa, buttermilk, vinegar). Of course, that natural reddish hue is a far cry from the day-glo v

ariety we generally see today in bakeries, and that’s where the magic comes in: very frequently, bakers accentuate the red with a bucket load of food coloring.

Commercially produced food coloring has been around since the early 1900s. Faced with reduced sales after the Great Depression, John Anderson Adams of Adams Extract began promoting a very red cake that elevated the red velvet cake to popular status among American housewives around the mid-century.

The “velvet” part of the cake’s name was an evolution, too. As early as the Victorian era, velvet referred to the fine quality of a cake’s crumb, which was enhanced by the use of cornstarch or even cocoa powder to soften the texture of the flour. Red velvet is likely a crossover: a red cake with a velvety crumb.

What tops the cake is another subject of some disagreement. Early recipes call for a boiled milk frosting, but somewhere along the line, it was eclipsed by no-cook frostings—most notably cream cheese frosting. In the 1950s, Pillsbury released a cookbook that included a recipe for a “red devil loaf,” and suggested frosting it with chocolate cream cheese frosting and garnishing with pecans. By the time the cake was dubbed red velvet in the ’60s, the recipes seem fairly split in terms of boiled frostings, no-cook frostings, and cream cheese frostings. So is one more authentic than the other? Not really. Recipes evolve for a reason, and the public demand for cream cheese frosting was simply higher than for other varieties—that’s the way that innovations become, over time, an authentic part of recipes like this much-loved one.

Red Velvet Cake

THIS IS AN OLD-FASHIONED RED VELVET CAKE, large and lovely. I’ve made some updates: the recipe calls for butter instead of oil or shortening, which I believe offers a richer flavor; as for frosting the cake, I’ve included a recipe for both of the traditional frostings, so you can choose your own adventure. And the food coloring? Yes, it’s there, and there’s a lot. It’s up to you how much to use—depends on whether you want a cake that whispers or one that shouts.

Makes one 8-inch layer cake (10 servings)

½ cup (1 stick) unsalted butter, softened

1½ cups sugar

2 large eggs

About 2 tablespoons red food coloring

2 heaping tablespoons unsweetened cocoa powder

2¼ cups cake flour

1 cup buttermilk

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1 teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon white vinegar

3 cups Cream Cheese Frosting or Boiled Milk Frosting (recipe follows)

Chocolate shavings, sprinkles, or red candies, for garnish (optional)

1. Position a rack in the center of the oven; preheat the oven to 350 degrees F. Grease and flour the bottoms and sides of 8-inch round cake pans.

2. In the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, cream the butter and sugar on medium speed until light and fluffy, 3 to 5 minutes. Add the eggs, one at a time, pausing to scrape down the sides of the bowl with a rubber spatula after each addition.

3. In a small bowl, make a paste of the food coloring and cocoa. Add this paste to the butter mixture, beating on low speed so that you don’t send drops of red coloring everywhere! Add the flour alternately with the buttermilk, ensuring that each addition is fully mixed in before adding the next. Scrape down the sides of the bowl with a rubber spatula after each addition. Stir in the salt and vanilla.

4. In a separate bowl, combine the baking soda and vinegar (it will fizz up). Immediately mix it into the batter until everything is combined. Divide the batter evenly between the prepared cake pans; smooth and level the batter with an offset or rubber spatula.

5. Bake for 22 to 28 minutes, or until a cake tester inserted into the center of the cakes comes out mostly clean. Let the cakes cool in the pans for about 10 minutes; loosen the sides from the pan using a small paring knife, then turn the cakes onto a wire rack. Let cool completely before frosting.

6. To assemble, set one of the layers on a plate with its flattest side up. Spread about one-quarter of the filling on top, stopping a little short of the outside edges of the cake. Add another layer of cake, press lightly, and repeat. Place your last cake on top and press lightly. Frost the sides and then the top of the cake with the remainder of the frosting. If desired, garnish with chocolate shavings, sprinkles, or red candies.

BOILED MILK FROSTING

Makes about 3 cups frosting

1 cup whole milk

¼ cup all-purpose flour

1 cup (2 sticks) unsalted butter, softened

¾ cup granulated sugar

Pinch of salt

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1. Whisk together the milk with the flour until smooth.

2. Transfer the mixture to a medium saucepan. Over medium heat, bring the mixture to a simmer, whisking continuously until it comes to a low boil. Remove the pan from the stove and transfer the hot mixture into a medium bowl; place plastic wrap directly against the milk’s surface to prevent it from forming a skin. Let cool.

3. In a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, cream the butter, sugar, and salt on high speed until very light and fluffy, 3 to 5 minutes. Stir in the vanilla and mix on medium speed for another 1 to 2 minutes.

4. Reduce mixer speed to low, and gradually pour the cooled milk mixture into the bowl. Increase the speed to high, and beat for 5 to 7 minutes; during this time, the frosting will become smooth and fluffy, which will give it a more pleasing texture and a more easily spreadable consistency.

ALL MIXED UP

I MAY GET IN BIG TROUBLE WITH THE SERIOUS BAKERS of the world for saying so, but I think that cake mix is a fine invention. True, the product is different than a cake made from scratch, but if the true secret ingredient is love, then cake mix has opened the door for many a timid baker to gain confidence in the kitchen. And believe it or not, playing up to the “made with love” aspect of baking is how cake mixes found an audience to begin with.

When cake mixes first debuted in the 1940s, they were a little different than they are today. They were actually far easier to assemble: all you had to do was add water, mix, and bake. And they were an utter failure. Not by the quality of the resulting baked goods necessarily, but in terms of sales.

But as I learned in Finding Betty Crocker by Susan Marks, General Mills made a little adjustment that added up to big results: they removed the dried egg from the mix, so that the home baker had to add a fresh egg (or eggs) before baking.

Turns out, the simple act of adding real eggs made a huge difference for home cooks: bakers felt more confident in presenting their creations as being “homemade” than their totally mixed counterparts. Of course, some naysayers will say that this was a happy accident, and that the dried egg in earlier mixes was omitted because it made the cakes stick to the pan.

Since the 1950s, cake-mix sales have exploded. They’ve also become popular as a “doctored” item, using recipes that start with cake mixes and then get far more elaborate from various mix-ins and clever techniques. These days, there’s even more love to add to mixes: some fancier ones (that are really not much more than pre-measured, sifted dry ingredients) will ask you to add egg, butter, oil, and other ingredients. At that point, one might wonder “Why use a mix, anyway?” The simple fact is this: While some continue to loathe, many continue to love, that inimitable cake-mix flavor.

IF YOU THINK “MARYLAND” AND “CAKE,” it’s likely that your first association is savory: after all, the region is legendary for their crab cakes.

Lovingly referred to as “frosting with the cake,” the Smith Island fools the eye into thinking it’s a regular layer cake.

But Maryland has some great sweet cakes too—most notably the Smith Island cake, a dramatic confection composed of between eight and fifteen thin layers of yellow cake, sandwiched with a very rich chocolate icing that sets up like fudge as it cools. This toothsome fudge not only holds the layers together, but it covers the top and sides of the composed cake stack.

Lovingly referred to as “frosting with the cake,” the Smith Island fools the eye into thinking it’s a regular layer cake—but once sliced into, the extraordinary striped interior of contrasting yellow cake and cocoa-hued filling is exposed.

The cake is named for tiny Smith Island, the only inhabited island off the coast of Maryland. Since this mini-island measures less than ten square miles, they clearly can’t build out—but they can build up, and they sure do, at least in confectionery form, with this architectural marvel. It shouldn’t be too surprising that this cake is the most famous culinary export from the island, and that its fame extends beyond the island to the entire region.

So who invented this amazing cake? If you ask locals, the standard response is the extremely helpful, “It’s always been here.” Well, “always” for Smith Island would date back to the seventeenth century, when the island was first settled by travelers from Cornwall and Wales. The settlers’ ancestry is still very evident today—aside from the cake, another notable feature of the island is the local dialect, a sort of Shakespearean English similar to what’s called Outer Banks brogue.

Clearly these islanders hold tight to their heritage, and this might give us a clue to the cake’s origins. It’s highly likely that Smith Island cake is the stateside adaptation of English tortes brought to the island by the early settlers. Perhaps the pencil-thin layers evolved as a sweeter and lighter version of the Welsh cake, a griddlecake, because the layers do resemble pancakes more than layer cakes.

So how did it get to be so sky-high? I think it had to do with some good old-fashioned, good-natured competition. On Smith Island, a time-honored tradition is the cakewalk, a game played sort of like musical chairs, but with a cake as the prize. The participants pay to play (usually, the cakewalk is held to raise money for charity), and a prize-worthy cake is vital to the good cause. A poorly stacked cake may not attract many players and as a result, not raise as much money as a more perfectly executed one. So the bakers of Smith Island started to stack layers as a form of competition, with the most impressive cakes growing to as many as fifteen layers.

The Secret Lives of Baked Goods

The Secret Lives of Baked Goods